A MIGHTY FORTRESS IS OUR GOD

A mighty fortress is our God,

a bulwark never failing;

our helper he, amid the flood

of mortal ills prevailing.

For still our ancient foe

does seek to work us woe;

his craft and power are great,

and armed with cruel hate,

on earth is not his equal.

Did we in our own strength confide,

our striving would be losing,

were not the right Man on our side,

the Man of God's own choosing.

You ask who that may be?

Christ Jesus, it is he;

Lord Sabaoth his name,

from age to age the same;

and he must win the battle.

And though this world, with devils filled,

should threaten to undo us,

we will not fear, for God has willed

his truth to triumph through us.

The prince of darkness grim,

we tremble not for him;

his rage we can endure,

for lo! his doom is sure;

one little word shall fell him.

That Word above all earthly powers

no thanks to them abideth;

the Spirit and the gifts are ours

through him who with us sideth.

Let goods and kindred go,

this mortal life also;

the body they may kill:

God's truth abideth still;

his kingdom is forever!

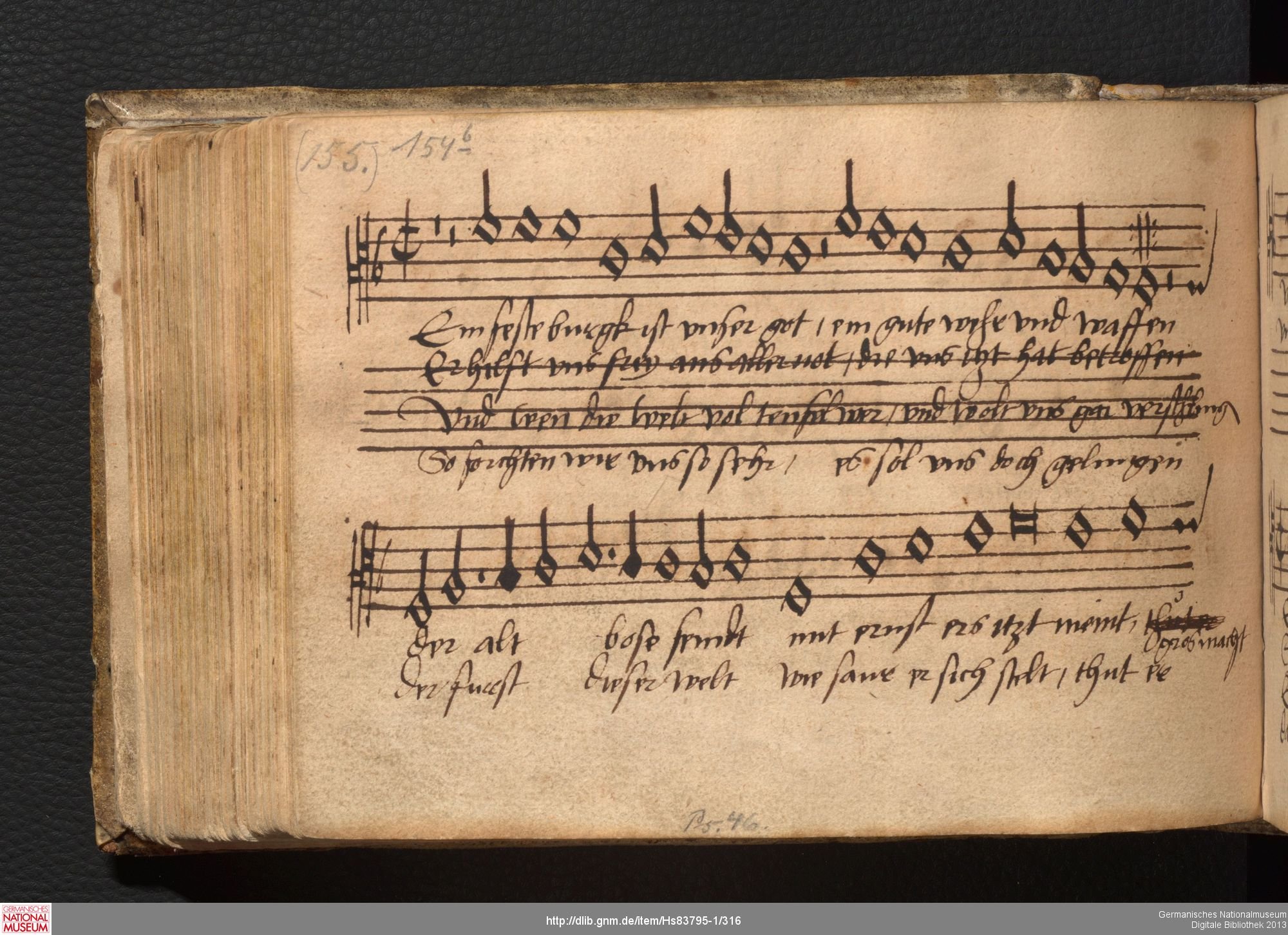

Few hymns have had as lasting an impact as “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”. Penned by Martin Luther some time before 1529, its imagery is triumphant and martial. It describes God as a fortress and a weapon against the Enemy, a military leader who will lead the Christians to victory over sin. The music, too, is impactful, especially in its original rhythmic setting. The original tune is dance-like and wouldn’t be out of place in a renaissance court ball. It is also characterised by trumpet-like melodic movement and all the militaristic connotations that trumpets carry. Given the times in which it was written, in which Protestants and Catholics regularly waged war against one another, this makes perfect sense. God is not just a metaphorical fortress against the devil, He is a very real defence against human enemies, both religious and political. The hymn reflects the worries and hopes of its time and its author.

What meaning does this hymn have for us today? Now that we are not embroiled in a bloody war between Protestants and Catholics, how can we reimagine the militaristic imagery of “A Mighty Fortress” for our modern church context?

A little background about myself, to help you understand my somewhat fraught relationship with “A Mighty Fortress”:

I was born and raised in the German Evangelical Church (EKD), which is an amalgamation of Lutheran and Reformed churches across Germany. One could say it is the heir to German Protestantism with alleverything that entails. I became Anglican as a student in the UK, but when I moved back to Germany, I found myself living in Wittenberg and working as an administrative assistant in a church institution.

“A Mighty Fortress” is omnipresent in Wittenberg. As you walk through the streets of the old town in summer, you’re likely to hear it being sung, the faint voices drifting through open windows of the various churches and assembly rooms.

And that’s not to speak of the chaos of Reformation Day, when the whole town practically quakes from the organ playing it at full volume (although I do admit that I enjoy that particular way of singing it.)

Every pilgrim who comes here wants nothing more than to sing this particular hymn in this particular place.

It’s amazing how quickly one can get tired of a hymn.

In fact, all things Luther have become somewhat burdensomecloyed for me after living in Wittenberg for two years. I associate them with work and duty, not with anything spiritual or historical. However, as much as I still do not look forward to singing it, there are some instances where I feel my relationship with the hymn might be healing.

Protestants aren’t particularly known for grand pilgrimages, and yet Wittenberg, the heart of the Reformation, has become something of a must-see for Lutherans. To stand in Luther’s church, to see his grave and the old town which has not changed all that much since his time, makes the Reformation and the reformer himself tangible. It brings to life the things many have only read about.

US Lutherans descend upon the town in their thousands every summer, to the point where both the ELCA and the Missouri Synod have permanent offices and representatives in Wittenberg. These churches run a large number of programmes, retreats, seminars, and workshops for Lutheran pilgrims.

The organisation for which I worked until recently also organises such events. Our outreach was global, inviting clergy and laypeople from across the globe to Wittenberg for two weeks of intense theological study. We had participants from Indonesia, Zimbabwe, El Salvador, and countless other countries. All our participants were Lutherans and all were excited to see the place “where it all began.” Many of them might not get another chance to visit the city.

Working with these groups gave me a different insight into Wittenberg and its quirks, and it also recalibrated my perception of “A mighty fortress”. Where I had previously sung it in the midst of a bored German congregation, or at a distance as part of the choir from the organ loft, now I was singing it in a group of people for whom this was an intensely spiritual and special moment. A group of people who saw this trip to Wittenberg as an opportunity to renew and refresh their faith, their calling, and their spiritual practice.

It made me reconsider my own cynicism and I decided to approach the text with fresh eyes. What can it give us in our modern context, even though the war it was written in has long passed?

Let’s read some excerpts of the hymn which really stood out to me.

“our helper he, amid the flood

of mortal ills prevailing”

I don’t believe this requires much explanation. A core part of our human experience has always been collective suffering. Whether from natural disaster, disease, or through human action, we have all felt the weight of suffering at one time or another. And yet we are reminded that God is with us through it all. A helper, a supporter. A fortress.

“And though this world, with devils filled,

should threaten to undo us,

we will not fear, for God has willed

his truth to triumph through us.

Let goods and kindred go,

this mortal life also.

the body they may kill:

God's truth abideth still;

his kingdom is forever!”

This second excerpt can be a little uncomfortable. Martyrdom is not particularly fashionable anymore, nor are we confronted with violent death as much as we used to be.

Or are we?

When we look at what is happening in the world around us, the illusion of safety and stability quickly crumbles. Suddenly the words “the body they may kill” are not some remnant of a past war, a mere metaphor to us. They are real and present. Whatever happens to us, God’s kingdom is forever. It will go on long after we are gone. It is something no one can erase through violence and killing.

We will not fear, for God has willed His truth to triumph through us.

It’s a powerful message, especially for those who have suffered violence. I’m sure it is a very different hymn for those who have experienced war first hand than for those of it who watch it from behind a screen.

Hymns are not bound to the words they contain. Each of us attaches a different meaning to them, shaped by our lived experiences and our hopes and fears. Whatever the original context or intent may have been, hymns, like all art, leave the artist’s hands and evolve independently.

For me, “A mighty fortress” is a perfect example of this. Luther would never have dreamt that this hymn would be sung in Zimbabwe or Myanmar, in languages he would never have heard of. There’s a beauty in that. It is a strange sort of musical communion with one another. We participate in the same act, singing the same melody, yet what we feel and experience in our hearts can differ greatly.

In the end, however, I believe we can all use the reminder of God’s steadfastness.